It wasn’t long after the firefight began that 1st Lt. Stephen Tangen ordered his platoon of soldiers on foot to get back to the armored trucks that had followed them up the Ghaki road and take cover.

The machine-gun fire was coming from insurgents across the valley floor from the dirt road that led to Daridam, a village on the northeastern border of Afghanistan that a battalion of American soldiers and their Afghan allies were on a mission to seize from the Taliban.

Staff Sgt. Eric Shaw told his eight-man squad, positioned just behind 60 Afghan soldiers who were leading the advance, to get down and return fire; he’d be back.

It was 100 degrees in the Ghaki Valley on the morning of June 27, 2010 — four days after Shaw’s 31st birthday, about a week after he’d arrived in Afghanistan and 2½ years before his wife would be presented with the Distinguished Service Cross for what he did to save the lives of 12 Afghan soldiers over the next few minutes.

“I always told him, ‘Don’t be a hero. Just come home,’ ” Audrey Shaw said last month.

That day, her husband didn’t listen.

EXCELLING AT HISTORY

Most of the rest of the 2nd Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division — nicknamed “No Slack” — had been patrolling Kunar province for more than a month when Shaw arrived.

He had stayed behind at the base in Fort Campbell, Ky., for the birth of his third daughter.

Julia, now 2, played with Play-Doh as her mother talked on the phone last month about the man whose photos hang throughout their home in Tennessee.

She was a sophomore at the University of Southern Maine in Gorham when they started talking at a party at the Sigma Nu house on School Street, where he lived.

“I thought he was cute,” Audrey Shaw said of her future husband, a senior history major who could do a dead-on impersonation of comedian Chris Farley and looked the part.

They dated for the rest of the school year and for a while after he graduated and moved back to Exeter, a town of about 1,000 people, 20 miles outside of Bangor. He had been raised there by his father, a Vietnam veteran who insisted he attend college instead of enlisting in the military after high school.

His mother, whom he reconnected with later, lived in Massachusetts with his three half-siblings.

“He didn’t have the best of everything” growing up, said Rick Whitney, Shaw’s U.S. history teacher at Dexter Regional High School.

Still, Whitney said, he was an upbeat kid, loud and fun-loving in a way that could make teaching class trying at times. “You had to love him though,” he said.

History was Shaw’s favorite subject.

“He knew facts, information, trivia that the other kids didn’t have a clue about,” said Whitney, whom Shaw would visit whenever he came home from college. “He said, ‘I’m going to school to be a history teacher, like you.’ “

Shaw also knew wrestling. A heavyweight in high school and college, he wasn’t the most talented athlete, but he studied the sport, said his USM teammate Jesse Peterson.

“He worked really, really hard,” Peterson said. “He was going to be a great coach.”

His college girlfriend imagined they might eventually settle down somewhere like Windham, and he could work in a local school.

ADVANCING IN THE ARMY

But a year after graduating from USM without finding a job, Shaw abandoned his plan to become a teacher and decided to join the Army. His father, who had died of lung cancer while Shaw was in college, wasn’t there to argue with him.

He called his girlfriend that summer to let her know he was going to enlist and asked if she wanted to come up north for a visit. They had broken up in March but got back together as soon as they saw each other again. Before he left for basic training in October, she was pregnant.

They got engaged around Christmastime, then in a phone call a week before the Easter holiday, he said, “Hey, do you want to get married next weekend?” Audrey Shaw recalled.

A justice of the peace wed them in her mother’s living room in Augusta.

In the meantime, Shaw had shed almost 100 pounds, transforming from an overweight frat boy into a toned fighter.

In September, four months after his first daughter, Madison, was born, he was deployed to Iraq for a 12-month tour, during which he’d earn his combat badge and a new rank.

The following year would bring another daughter, Victoria; another deployment to Iraq, this time for 15 months; and, at the end, another promotion — to staff sergeant.

That’s the only rank Tangen ever knew him as. The young West Point graduate, who had just finished officer training, joined Company C six months after Shaw got back from his second tour.

“He probably walked up to me and said, ‘Who the hell are you?’ ” Tangen said.

It’s unusual to know someone outside of your platoon, Tangen said, but people knew who Shaw was. A couple of months later, Shaw joined Tangen’s platoon as a squad leader, and the new officer learned a lot more.

“As a lieutenant you’re taught you should always be the first one to do something, lead from the front,” Tangen said. “If I showed up to work at 5 in the morning, he’d be there at 4:55.”

Shaw was always the first to arrive and the last to leave, Tangen said. And, unlike some staff sergeants, he never hesitated to get down in the dirt with his men.

But if Tangen ever thanked him for his hard work, he’d shrug it off.

“It was never anything he looked for,” Tangen said.

That same attitude was apparent at home. He got angry when his wife put Army stickers on the back of their Ford Taurus. It was just his job, he told her.

“He never wanted recognition for anything he did,” she said.

Eventually, he would have no choice.

MISSION TO REMOVE THE TALIBAN

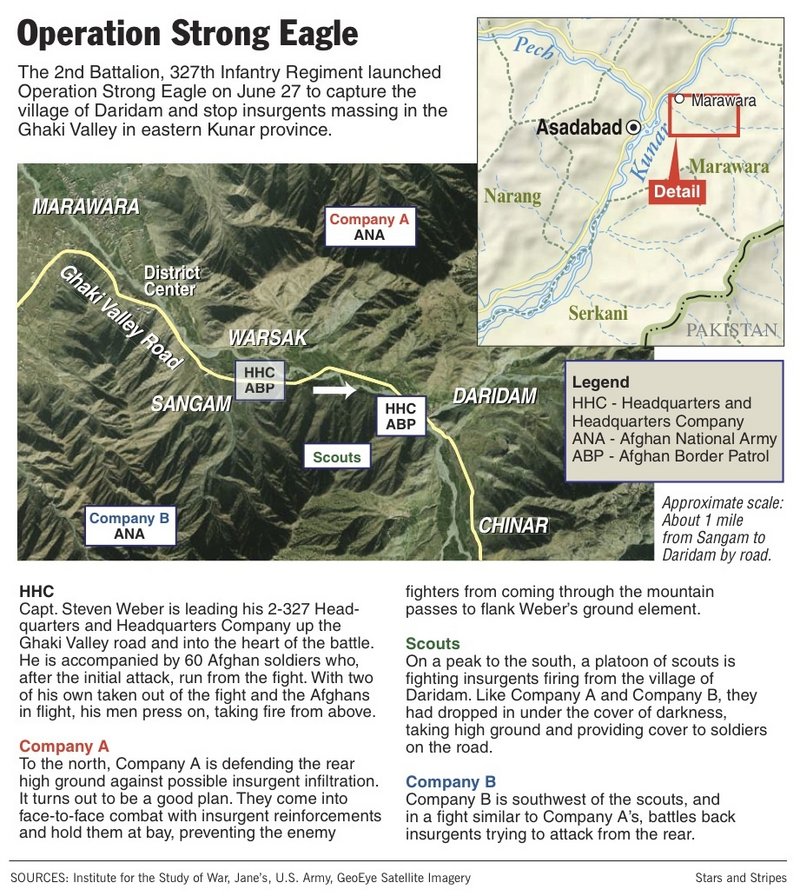

Just before Shaw got to Afghanistan, his platoon was told about Operation Strong Eagle.

Insurgents had been encroaching from the Pakistani border with their sights on Asadabad, the capital of Kunar province. They were barging into homes, terrorizing villagers in the valley.

“There were reports of murders and thefts,” Tangen said.

The purpose of the mission was to remove the Taliban from the valley — and the threat to the Afghan people and their government.

It was around 1 a.m. on a Sunday when the U.S. troops, in a line of vehicles a kilometer long, left Forward Operating Base Joyce for Marawara District Center. There they joined the Afghan National Army and the Afghan Border Police, together a force of more than 400 soldiers.

Tangen’s platoon had been detached from Company C to join Headquarters and Headquarters Company, which with the Afghan soldiers would lead the advance to Daridam up the valley road.

As they coordinated their attack, three units of American soldiers were dropped by helicopter in the middle of the night onto ridges that lined the road, which was cut into the mountain on the south side of the valley.

Decades earlier, Russian soldiers had been tripped up by the narrow road, and disabled vehicles at the front of the line had led to their demise.

Knowing that, the U.S. and Afghan troops would lead with soldiers on foot — the 60 members of the Afghan National Army, followed by Tangen’s platoon of 14 men with Shaw’s squad in front and eight armored vehicles behind them.

From where they left the rest of their trucks, they walked two kilometers before the first rocket-propelled grenades hit, killing one Afghan soldier, blowing the leg off another and marking the start of the battle.

The insurgents were shooting from cutouts in the mud walls that surrounded buildings in the village on the north side of the valley, almost a half-mile away.

Bullets whizzed, cracked and chipped at the mountainside. The Taliban were too far away to take accurate shots, and Tangen knew it would be even harder for them to hit troops behind armored vehicles.

But the trucks had stopped moving once the gunfire began, and they were out of sight of the soldiers who had walked past a knoll in the road.

GIVING HIS LIFE TO HELP ALLIES

Tangen told his platoon to get back to the line of trucks and then got on the radio to get the vehicles to move forward. He didn’t see Shaw leave his squad and run up through the Afghan soldiers to relay the message to their leaders, but he heard about it later in a debriefing.

“The whole way he was helping the Afghans get behind the trucks,” Tangen said of Shaw, who yelled and used arm motions to beckon them. They spoke only Pashto, and he spoke only English.

But besides the language barrier, the Afghan soldiers were uneducated and under-trained. Most couldn’t read beyond a third-grade level, Tangen said. When they started getting shot at, they shot back, but not necessarily toward the insurgents.

“There was definitely an initial degree of confusion,” said Tangen.

Shaw kept his promise to his squad — that he’d be back — and got beside the first truck in the line. Tangen was beside the truck behind him.

But there were still a handful of Afghan soldiers in front of the vehicles, who weren’t responding to Shaw’s signals.

He had not hesitated to get the Afghans to safety before and didn’t think twice about helping them again. But this time, Shaw’s decision proved fatal.

Just as he stepped out in front of the truck to grab the exposed Afghan soldiers, he was hit.

The force to Shaw’s face twisted his body and toppled him over as if he’d been tackled by an NFL player, Tangen said.

He grabbed onto Shaw’s armor and pulled his body back behind the vehicle.

“That’s when I realized he had died,” Tangen said, though it had probably happened before he hit the ground.

Recounting the incident from Fort Campbell last month, Tangen spoke slowly, pausing as he approached the moment he saw his comrade killed. But at the time, he had to do his job.

Following protocol, he reported the casualty over the radio by reading the unit code for Shaw’s company, the first two letters of his last name and the last four digits of his Social Security number.

The voice on the other end asked who.

“I told him it was Shaw,” Tangen said.

The firefight continued until sunset, but the Afghan soldiers had retreated from the battlefield by the afternoon.

About the same time Shaw was killed, another American soldier, Sgt. David Thomas of St. Petersburg, Fla., was shot dead on a ridge south of the Ghaki road where Company B was battling another group of insurgents.

Those would be the only fatalities of the fight for the U.S. troops. By the time the Afghan soldiers rejoined them in the morning, the insurgents were gone.

Tangen was supposed to leave the next day for another job.

“I told my commander, I begged him to let me stay to help those guys get back on their feet from the loss they had,” he said. “Everyone looked to (Shaw) for strength, for leadership, for everything. He was the rock of the platoon. His death was devastating.”

HEARING A KNOCK AT THE DOOR

Meanwhile, Audrey Shaw and her daughters had been in Maine, staying with her mother in Augusta for the summer before Madison started kindergarten.

Audrey Shaw was watching television just before 10 p.m. on the same day as the battle, when she heard a knock. She thought it might be Tori, her middle daughter, giving her grandmother a hard time about going to bed by kicking the wall.

She got up and walked to the door anyway, but didn’t see anything in the dark. When she looked back, she noticed something shift outside the glass of the French doors, then saw the shine of the gold buttons on a Class A uniform. Two soldiers were staring back at her, which she knew could only mean one thing.

She had always told her husband, if it came to this, she wouldn’t open the door. But, after a few long seconds standing there, she knew she had to.

One of the men asked if she was Audrey Shaw, wife of Staff Sgt. Eric Shaw.

“I just stared at them and looked straight forward and said, ‘Is he dead?’ ” she said, even though she had been prepped at the base for what to expect.

“I said, ‘Of course, he’s dead. There’s two of you. You’re a chaplain,’ ” she said. “They stopped asking who I was.”

She flew the next day to Dover, Del., to meet her husband’s body as it landed on American soil. In a metal box, covered with the flag, he was taken to a mortuary and a week later, flown back to Maine.

She requested the autopsy report, which cited the cause of death as a ballistic wound to the head. There was also a disc of photos. She hasn’t put it in a computer.

She didn’t tell her daughters until just before the wake. Madison, the oldest, had asked her father a week before he left what would happen if a bad guy shot him and he died.

He later told his wife: “I told her she wouldn’t see me anymore, but that I would always be able to see her.”

When she sat her daughters down to tell them he had gotten hurt at work, Madison started crying right away.

“She knew what dead was,” Audrey Shaw said.

HONORED FOR SAVING 12 LIVES

A couple of months later, she got her own debriefing about the incident, which was when she found out he had been nominated for a Distinguished Service Cross, an award second only to the Medal of Honor.

Despite persistent phone calls, she learned little about the progress his nomination was making through the review process for two years.

Any step of the way, someone can request more information, and the review starts over, Tangen said. Every time that happened, he was the first person to find out.

“When it’s a soldier who died right in front of you, who you love, it’s emotional to be told he doesn’t deserve it,” Tangen said.

During that process, he started to feel strongly that Shaw’s actions warranted a higher distinction.

“His final act, his final thought, was to save a human life that was not an American soldier,” said Tangen, who doesn’t know of any Medal of Honor recipients who did the same for Afghans. “He stands alone.”

The citation for the Distinguished Service Cross says Shaw’s “bravery and selflessness saved the lives of twelve Afghan soldiers and enabled the forces to consolidate, continue fighting and accomplish the mission.”

A plaque was presented in January to his widow and his mother, Michele Campbell, who flew in from Rhode Island for the ceremony at Liberty Chapel on the Kentucky base.

“I looked around. I couldn’t see anything but wall-to-wall people,” Campbell said.

Tangen is confident that the award will help Shaw’s story be retold.

“Some soldier, someday will be just like him because of what he did,” he said. “You can’t ask for really much more than that.”

For now, Audrey Shaw said she’s keeping the cross in a trunk with her husband’s other medals. She’ll put it on display once her daughters are old enough that they won’t take it down or try to color it.

At least one of them, however, has already grasped the significance.

“My oldest told me she wants to be in the Army,” she said, “because she wants to be a hero, like Daddy.”

Staff Writer Leslie Bridgers can be contacted at: 791-6364 or at

lbridgers@pressherald.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.