BEIRUT — Syrian government forces unleashed artillery attacks and air raids in eastern Damascus on Wednesday in a campaign that followed unverified reports of mass deaths in a chemical weapons attack.

Those allegations of gassing civilians — opposition activists claim that 1,100 to more than 1,600 people are dead — dwarfed all previous such accounts in the increasingly bloody civil war.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights reported that 647 Syrians were killed Wednesday, and it attributed nearly 590 of those deaths to chemical weapons. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, considered the most authoritative group tracking casualties in the conflict, estimated at least 136 dead from an air assault but didn’t address whether chemical weapons appeared to be involved.

Wednesday’s offensive appeared designed to wipe out recent rebel gains outside the capital, but it was overshadowed by fresh claims from rebel activists that the forces of President Bashar Assad deployed chemical weapons even as international inspectors arrived in his country.

Few reliable details filtered out of the country — more than two years into a civil war – to confirm or refute reports of a chemical attack. Information about any munitions and whether they included nerve or chemical agents couldn’t be confirmed without independent observers in the area that allegedly was attacked.

Instead, scores of amateur videos posted online showed dozens — women, children and men identified as civilians — either dead or in deep respiratory distress and medical crews frantically trying to treat them.

What was clear was that the regime had mounted a major attack on a series of restive, pro-rebel neighborhoods on the eastern outskirts of the capital.

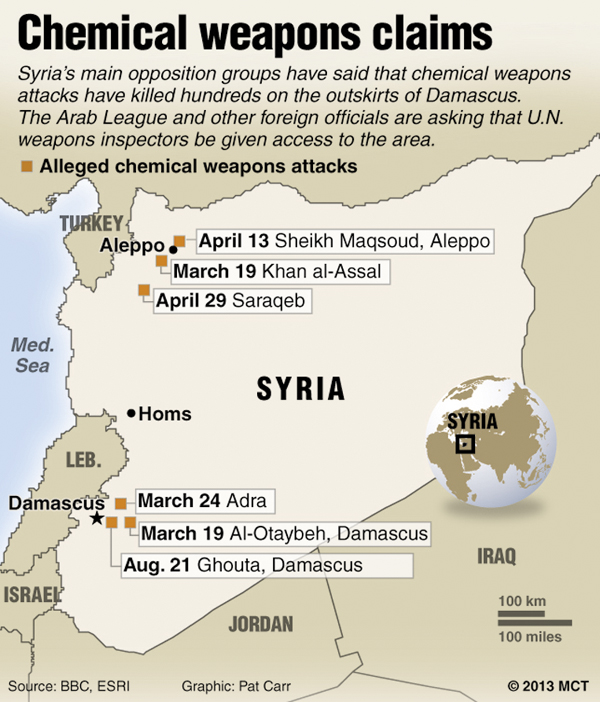

The claims of a widespread chemical weapons attack on a dense urban area came as United Nations inspectors arrived to investigate previous allegations that the regime had used banned chemical weapons earlier this year.

Syrian state media denied Wednesday that chemical weapons had been used.

The U.N. Security Council met in closed session Wednesday to talk about allegations of the world’s largest chemical weapons attack since the 1980s.

Even without confirmation, the reports of chemical weapons use put the U.S. government in an increasingly awkward position over what role it ultimately will play in a seemingly intractable civil war in a volatile region.

A finding that Assad’s military was gassing civilians would be the clearest example yet of a breach of the “red line” that President Barack Obama had warned the Syrian leader not to cross. And it might crank up pressure for more direct military aid to the rebels, loosely knit factions increasingly infiltrated by foreign fighters with links to al-Qaida terrorists.

Greg Thielmann, a senior fellow at the Arms Control Association in Washington, said the scale of the alleged attack far eclipsed a previous U.S. assessment. Washington earlier had concluded that the regime had conducted only small-scale attacks at different sites, with a total of about 150 victims.

“This would seem to be a major event,” Thielmann said, “but it’s difficult to sort out what allegations are credible and reliable.”

The latest charges imply that the Syrian government deployed banned weapons at the same time that international observers arrived to investigate earlier rebel claims of their use, and longtime observers found the timing nonsensical.

Still, rebel leaders and opponents of the Assad regime insisted that it was newly guilty of war crimes.

“The chemical weapons massacre had more than 1,500 martyrs and 5,000 wounded, most of them women and children,” said Abu Mansour, an activist based in the area of Reef Damascus. He claimed that chemical munitions were dropped on the suburbs of Ein Tarma, Zamalka and Jobar.

Mohammed Salaah al-Din, another activist from the area, said sarin gas shells began to hit the area shortly after 2 a.m. Wednesday. He claimed that some 1,650 people were dead, that 5,000 had been wounded and that physicians had confirmed the presence of the nerve gas.

Mutasem Billah, a rebel supporter from the outskirts of eastern Damascus, said by Skype that he’d seen a chemical weapons strike less than a half-hour later. He counted 29 rockets that he said were armed with chemical warheads.

“They were launched at five points in the eastern Ghouta, and the doctors told us that it was sarin gas,” he said. He estimated the dead at 1,160 and the wounded at closer to 7,000. “Most . are women and children.”

Their symptoms, he said, included vomiting, panic attacks and contracted pupils.

The activists who made the claims conceded that they hadn’t yet had time to smuggle blood and tissue samples out of Syria — they’ve done so before — to confirm the use of nerve gas.

That left experts with only inconclusive videos to analyze. One forensic expert questioned whether panicked victims assumed they’d been hit by nerve agents and then misused medicine.

“There seem to be increasing amounts of footage of very realistic-appearing injuries commensurate with a chemical attack, but (that is) still leaving lots of questions,” said Stephen Johnson, a visiting fellow at Cranfield University’s Forensics Institute in Great Britain. “It would appear that patients have been injured by what might be a rapid attempt to inject atropine,” a potentially poisonous compound that’s sometimes used as an antidote to sarin exposure.

Johnson noted that videos had moved to the Internet quickly early Wednesday. More typically, footage from the rebel side is posted gradually over the course of a day or longer. It can be difficult to access the Web in the area amid regular power outages and ongoing fighting.

Still, some of the symptoms are commensurate with exposure to nerve gas, “which might be sarin,” he said. “But you can’t tell that in a video.”

Thielmann, the arms control specialist, thought the White House was correct to be cautious before targeting Syria’s chemical weapons facilities.

“The knowledge is always imperfect, and we don’t always know where these things are,” he said. “In some ways, we are safest with the Syrian government maintaining control of these assets.”

The Syrian army is widely thought to have extensive Cold War-era stockpiles of chemical weapons. Whether the government’s military forces have used it, however, has been open to debate.

American and European officials have said that deploying chemical munitions would cross a “red line,” likely forcing them to intervene in the conflict with military might.

A revelation that some chemical weapons might have been used in previous attacks — apparently verified in blood and tissue samples that activists smuggled out of Syria — led Obama to announce his willingness to arm some rebel groups two months ago.

At the White House, spokesman Josh Earnest said the president condemned any use of chemical weapons in Syria. Earnest said the United States had no independent evidence of the use of chemical weapons but that it urged Syria to allow the United Nations investigative team to gather evidence.

“The use of chemical weapons is something that the United States finds totally deplorable and completely unacceptable,” he said. “Those who are responsible for the use of chemical weapons, if it’s determined that that’s what happened, will be held accountable.”

Earnest said Obama and his aides were reviewing the situation and that he had no policy changes to announce. He did say the president “wouldn’t rule out additional assistance.” Already, the United States is providing the largest amount of humanitarian aid to Syria.

Tamara Cofman Wittes, the director of the centrist Brookings Institution’s Saban Center for Middle East Policy in Washington, said that even evidence of chemical weapons use in Syria might not be enough to prompt U.S. intervention. She sees an “erosion” of Obama’s red line.

Since the first U.S. warning about chemical weapons, the Syrian battlefield has changed. Jihadists have taken a lead role in the rebel movement, while the regime got a boost from Hezbollah militants and from Iranian and Russian arms.

As the war has ground on, U.S. officials have become increasingly vague about what would force an intervention.

“I’m not sure the chemical weapons issue is as much a determinant of policy as it was,” Cofman Wittes said. Until last year, she was a chief coordinator of the administration’s Arab Spring response from the State Department and was the deputy assistant secretary for Near Eastern affairs.

She noted that Obama’s remarks in a TV interview with Charlie Rose in June suggested that the administration’s red lines had faded. In that appearance, Obama made it clear that he’d proceed with caution in response to any chemical-weapons claims.

“Have we mapped out all of the chemical weapons facilities inside of Syria to make sure that we don’t drop a bomb on a chemical weapons facility that ends up then dispersing chemical weapons and killing civilians, which is exactly what we’re trying to prevent?” Obama said. “Unless you’ve been involved in those conversations, then it’s kind of hard for you to understand the complexity of the situation and how we have to not rush into one more war in the Middle East.”

Cofman Wittes said that a confirmed chemical weapons attack could help the United States nudge Russia, which has strongly backed Assad over international objections.

“If there’s evidence of regime use of chemical weapons,” she said, “it certainly puts greater pressure on countries like Russia that give cover and protection to the Assad regime.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.